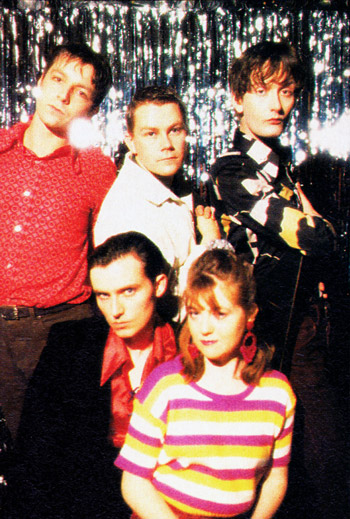

Words: Tony Marcus, Photographer: James Fry

Shot at the Wag Club

Taken from i-D Magazine, December 1993

Post-Suede, Pulp could be the next

'70s-influenced glam indie band to make it big. And

singer Jarvis Cocker has all the charisma necessary for

pop stardom.

Shopping at jumble sales, reckons Jarvis Cocker, links us to the cavemen. "It fulfils our primal needs," he explains. "We feel that we have to go out into the world and find things. When people were primitive they would hunt for things like food to eat. We don't need to do that anymore. So we hunt for other things. I hunt through Oxfam shops and jumble sales." Jarvis is lead singer with a band called Pulp. He's tall and thin, favours the effete, tight fashions of the '70s, speaks with a Sheffield accent and sings like he wants to be Serge Gainsbourg, Julian Cope and Scott Walker, all at the same time. He writes difficult love songs about incest, sexual frustration on council estates and people whose dreams turn to dust. The band back him with a thrashy '60s party workout, duelling Stylophones and thick melodies from ancient synthesisers.

Pulp are the ultimate Oxfam band, with Jarvis's polyester shirts and a sound that's influenced by the easy listening discs that junk shops put in a box marked 50p. "Pulp keep using everybody's cast-offs, the things other people have rejected," says Jarvis. He's wearing an old LCD wristwatch, the kind that tells the time in flashing electric red when you press the button.

Together since 1981, Pulp used the '70s before Suede and Denim, and light entertainment before Vic and Bob. Jarvis is a glamour queen drawn to the flared collars, crooners, lipgloss and razzmatazz that are easily dismissed as kitsch. "I would never say that I had bad taste, although other people may think I have. The whole essence of any glamour thing is that you can't be tongue-in-cheek about it, you have to be sincere about it at the time you're doing it, you have to believe in it." He traces his interest in glamour to childhood. "I used to take Batman really seriously, that was the first thing I got into. My mum made me a cape, I wore some purple woolly tights and I had a Batman mask. I used to go shopping with her dressed as Batman."

And then he wanted to be a pop star. "It's part of living in a fantasy world, it gives you a way of justifying yourself, which I've needed a lot in the past. A week might end and I might think about what's happened: not very much. At least I could say, 'oh well I'm in a band. I'm trying to do something, maybe things will improve'."

And they very nearly did when Pulp recorded a 'legendary' bunch of songs for John Peel's influential radio show. "I thought I was going to be a child star," recalls Jarvis, now 30, of the session broadcast when he was 17. What happened then? "Exactly, you tell me." Nothing happened, and Pulp began "seven years of pain" where they signed on, toured, took day jobs, changed line-ups and ran into contractual problems with small record companies. Stuck in Sheffield, Jarvis believes he came close to cracking up, filling his room with black bin bags full of jumble sale purchases. "Maybe it was some kind of way of getting myself security or something. I would never really bother taking it out of the bags, just getting it was the thing. Towards the end I could hardly get into the room."

At this stage, Pulp, says Jarvis, were the archetypal indie band writing songs about fear and failure. "I was worried I was going to turn into a marginal eccentric. I didn't want to end up like a freak and I remember we made a record called Freaks because that's what I was scared of. Quite grim." Jarvis realised that his chances of being a pop star were fading so he approached St Martins College Of Art to study film. "I'd heard about St Martins, read about it in books, and thought this is going to be the glamour I've been looking for, there in the capital city it will occur. Of course it didn't."

And then, over a decade after that first Peel session, Pulp found themselves. Jarvis became the perfect indie pop star as he finally outsmarted his neuroses. He found artistic distance, maybe through film or maybe because he had simply got older and outlived them. Pulp still weren't greatly successful, releasing singles on Sheffield's indie label Gift, but they were wiser. Jarvis applied irony to songs about failed love and creative, passionate people who "ended up having their wings broken". His viewpoint was matched by a band sensitive to the painful echoes of broken teen-dreams in kitsch pop epics.

"You might go out clubbing and see someone and think they're living the life, they're doing it. But the chances are they probably go home and the electricity's run out or they've got no money left for the rest of the week. It's always a front but it's a very seductive front."

Jarvis writes songs about girls who use nightlife, lipgloss and infidelity to bridge the gap between dreams and bare reality. Into the tawdry, kitsch and misguided, he reads flickering hope and growing despair.

"I wouldn't like people to think that I'm writing songs from a distanced point of view. All the things I write about have happened to me or people that I know. If there's any sarcasm there, it's directed as much at myself as anyone else." The Pulp perspective is rooted in the fact that Jarvis has been there. A wannabe popstar on housing benefit and the brink of breakdown. Bittersweet elders, Pulp can at once identify with and distance themselves from the suffering in Jarvis's songs. "It is still entertainment." he stresses, "we're not there to provide some kind of exercise in giving people pain."

Pulp entertain with kitsch references, Stylophone whoops, and a fusion of Burt Bacharach, Hal David, Serge Gainsbourg and the Rolling Stones. They have a bizarre alchemy of daftness where they transform embarrassing, neurotic, sad things into charisma. Recently signed to a major label for the first time, they're the closest they've ever been to success.

"I grew up," remembers Jarvis, "with the space programme and TV shows like Star Trek and Space 1999. I really believed that I would grow up in the space age and travel to those other planets. The change that's occurred to me now is that I think maybe it wouldn't be that great. If they colonised Mars, there would be problem estates on it within a decade, and people would look for a minority to oppress and start Martian-bashing or something."